Most mobile solutions are built and operate in a distributed architecture where services play a prominent role for providing data and applying business logic.

Let us take an example of a hotel reservation mobile app:

- When the user specifies the desired target city, a back end service would provide the list of available managed/operated hotels at this place.

- Once he or she specifies the desired stay period, the service would filter the above list to provide those having free rooms for that period.

- When the user selects a room and applies for the reservation, the service would then register that reservation, proceeds to payment… etc.

It is hardly imaginable for such an app to operate independently from a back end service.

The price of distributed apps

In the previous example, the mobile app presents and manipulates several objects: the place (city/location…), the hotel, the room… etc.

Information about each of these objects is obtained from the service. The structures (metadata) of objects transmitted by the service should obviously match those handled by the mobile app.

In a typical (SOAP) situation, using Visual Studio for instance, your mobile app project would reference the service. Through the service's WSDL file, Visual Studio would generate the code for objects (classes) and operations defined by that referenced service.

If one of service's objects structure changes, you have to relaunch the process to update your app's service reference so that your objects' metadata be in sync with those defined by the service. If you don't do this, your app will simply crash at the first service call involving any unmatched object!

After each single change, deploying the solution's components (service / client app) become also a big hurdle.

In a few solutions, that may be desirable (or required). In most, the hurdle surpasses the benefits. It is hardly sustainable in a large solution. Actually it is not even sustainable when you are the sole developer of both components!

Resorting to use REST instead of SOAP (you may combine both) does not solve the difficulty, as that only changes the serialization format.

Using one single object

Let us imagine a service whose operations return always the same object. That would be quite handy independently of that object's serialization format.

In several large solutions I came to explore during last years, aggregating services responses into an abstract object, say, ServiceResponse was a common design practice. A given service operation response may look like (wsdl):

<element name="Operation1Response">

<complexType>

<sequence>

<element name="Operation1Output" type="Operation1OutputObject"/>

<element name="ServiceStatus" type="ServiceStatus"/>

</sequence>

</complexType>

</element>

With this, you know that any service operation you may call will always return a structure containing your expected object along with a service status object.

That approach seems good. Still it is going half way in abstraction, because you still should know the exact structure (metadata) of the expected object. And hence doesn't solve the evolution and deployment hassle: if, for some reason, you change the service's object structure, all your consumers should sync this change before deployment. The deployment of a new service version requires the deployment of a new consumers' versions… big hassle = increased risks.

Back to property bags!

I previously talked about property bags (here and here…).

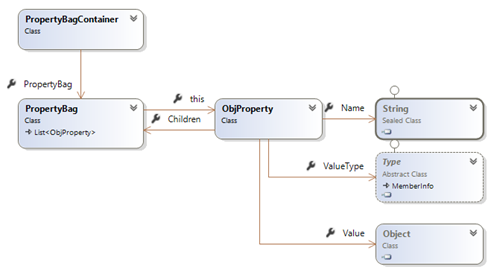

A short reminder:

With that simple structure we are able to represent virtually any object in a strongly-typed manner.

Using property bags, we can imagine a unique structure for our service response. Which may look like this (wsdl):

<element name="ServiceResponse">

<complexType>

<sequence>

<element name="OperationOutput" type="PropertyBag"/>

<element name="ServiceStatus" type="PropertyBag"/>

</sequence>

</complexType>

</element>

Now, when we call any service operation, we know in advance that it will return an output property bag, accompanied with a status property bag.

Each element of our property bag being strongly typed (specifies its data type), we can easily convert the received bag to the expected object.

That conversion itself can be subject to a set of business rules. But that would be implemented 'once' independently of service or consumer versions and deployment constraints.

This approach doesn't eliminate the need for a unified business model. It enforces its usage.

By creating a loose coupling mechanism between services and consumers it allows more separation of concerns and minimizes evolution and deployment risks.

Exercise: service side code sample

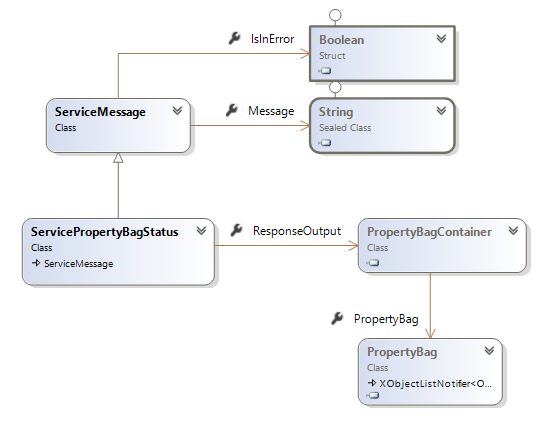

Let us define service response as:

[DataContract(Namespace = "")]

public partial class ServicePropertyBagStatus : ServiceMessage

{

PropertyBagContainer _responseOutpput;

[DataMember]

public PropertyBagContainer ResponseOutput

{

get { return _responseOutpput; }

set { _responseOutpput = value; }

}

…

…

Our response structure would then look like (wsdl):

<complexType name="ServicePropertyBagStatus">

<complexContent mixed="false">

<extension base="ServiceMessage">

<sequence>

<element name="ResponseOutput" type="PropertyBagContainer"/>

</sequence>

</extension>

</complexContent>

</complexType>

Sample code of a service operation (for reading a customer data) may look like this:

[OperationContract]

public ServicePropertyBagStatus GetCustomer(int customerId)

{

return SvcUtilities.LoadCustomer(customerId);

}

Our service utilities module method LoadCustomer:

public static ServicePropertyBagStatus LoadCustomer(int customeId)

{

ServicePropertyBagStatus status = new ServicePropertyBagStatus();

if(customerId == 0)

{

status.SetErrorMessage("No value provided customerId");

return status;

}

// load the customer's info from database server

Customer customer = Customer.LoadDbUser(customerId);

// extract this object's data contract into a property bag container

status.ResponseOutput = ExtractPropertyBagContainer(customer.GetType(),customer);

// return the service response status

return status;

}

Extract the object's property bag:

internal static PropertyBagContainer ExtractPropertyBagContainer(Type type, object obj)

{

// get soap xml of the object's data contract

DataContractSerializer serializer = new DataContractSerializer(type);

MemoryStream stream = new MemoryStream();

serializer.WriteObject(stream, obj);

// parse the soap xml into a property bag container

PropertyBagContainer container = PropertyBagContainer.ParseXml(stream, true, null);

stream.Close();

return container;

}

Some Property bag container helper methods:

public class PropertyBagContainer

{

protected PropertyBag _bag;

// parse an object into a property bag container

public static PropertyBagContainer ParseObject(object obj, ObjProperty parent);

// parse xml stream into a property bag container

public static PropertyBagContainer ParseXml(Stream stream, bool parseSiblings, ObjProperty parent);

// parse xml node tree into a property bag container

public static PropertyBagContainer ParseXml(XElement xnode, bool parseSiblings, ObjProperty parent);

}

Client side code sample

Our service operations will now return a Property Bag Container containing the expected object's property bag. A helper static method of PropertyBag (AssignObjectProperties) allows us to assign its content to a specific object:

public static bool AssignObjectProperties(object targetObject, PropertyBag bag)

We can thus write:

public bool ParsePropertyBag(PropertyBag bag)

{

return PropertyBag.AssignObjectProperties(this, bag);

}

Assigning property bag contents to an object is done by assigning values of the bag items to object's properties having the same name and data type. Extra logic can be introduced here according to your business requirements (for instance: checking object integrity through specific attributes).

Now, on the service consumer application, assume we have a service that is referenced as CustomerService. We may call the service's LoadCustomer operation like in the following code:

public bool LoadServiceCustomer(int customerId)

{

CustomerService proxy = new CustomerService();

var status = proxy. LoadCustomer(customerId);

// we may check the service status for errors here

….

// assign received properties to this object

return this.ParsePropertyBag(status.ResponseOutput.PropertyBag);

}

Client side with Json

The process is the same in a REST configuration (You may see some details about WCF REST services here) as you actually will always receive a ServicePropertyBagStatus object independently of the transmission format (xml / json… etc.). Parsing the received response into a property bag container can be done using components like the .Net NewtonSoft.Json:

HttpWebRequest request = (HttpWebRequest) WebRequest.Create(url);

string str = GetResponseString(request);

ServicePropertyBagStatus response = JsonConvert.DeserializeObject<ServicePropertyBagStatus>(str);

PropertyBagContainer container = response.ResponseOutput;

…

…

You can download the property bag binaries (std + portable) here.